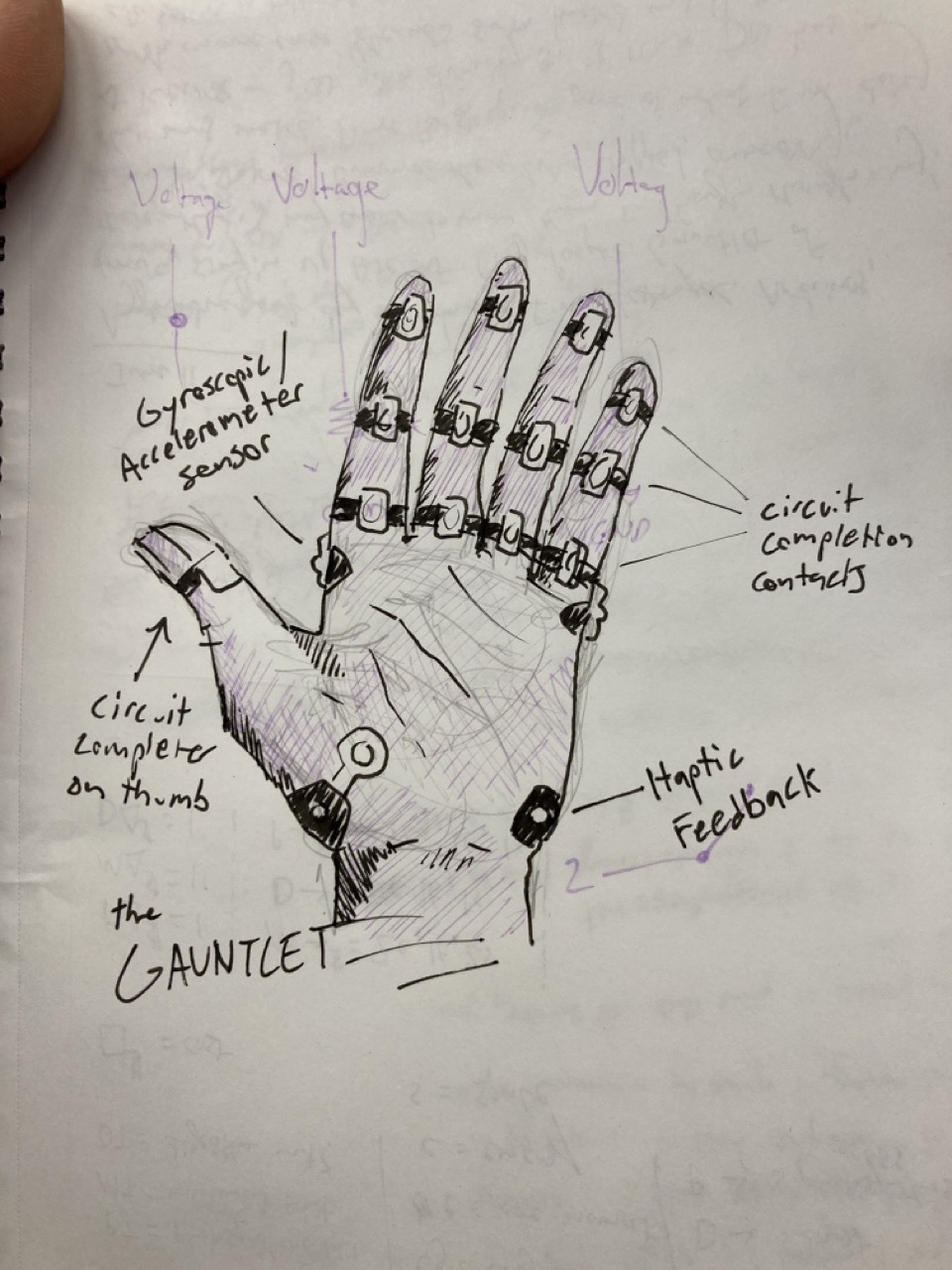

The Gauntlet: What is it?

The Gauntlet is a wearable experiment. It’s an investigation of what other computer interaction possibilities the human hand may be capable of.

The basic idea is that a grid of inputs can be spaced out across the pads of each finger so that an entire keyboard can essentially be emulated by pressing the thumb against the correct contact pad. However, each finger really only has three segments, and 8x3 is only 24. That’s 3 sort of the 26 letters of the alphabet and even less adequate to represent all of the options of a keyboard like the one I am typing on right now.

Input Limitations and how to get around them

However, keyboards cleverly multiply their input potential with combination keys like shift, control, alt and command. On a glove, where real-estate is precious, my strategy is to introduce new dimensions of input to sit next to the “contact creation” dimension.

Here are some options for those dimensions:

- Gesture: I have 3 axis accelerometer/gyroscope sensor that can detect the angle of the hand, similar to what Imogen heap does (see the inspiration section below)

- EEGs: this one is a bit out there, but consumer grade EEGs are capable of outputting a few signals at least, mapped to particular thoughts. They’re a bit finicky as the signature of a thought is specific to an individual, and they may not be super specific, but how cool would it be to control input with the mind?

- More contacts: pretty simple. Just fit more contacts onto the hands somehow.

Activation

I also want to mention that I’d like to use additional contacts to do things like turn the gloves on and off, so that this input can be stopped whenever the user wants to use their hands for normal things without a risk of the equivalent of a cat running over the keyboard.

Implementation

I am starting with an arduino nano, which is a type of small microcontroller capable of delivering power to a circuit as well as detecting both digital and analog changes in that circuit.

My basic plan is to take advantage of the analog sensing capabilities by creating “resistor ladders”, where different segments of a circuit are broken up by resistors so that completing them in one place will produce a different voltage reading than another place.

This is not a perfect example - I sort of messed up this example in that the voltage sensor on the arduino reports a max value of 1023, and I’m not really adequately breaking up the resistors to get that full range.

Here is an breadboarding example with a circuit on the glove itself:

And here is an example of the differences in voltage being used to send some sort of output behavior:

That’s as far as I’ve gotten so far, but more to come!

Inspiration

It is very inspired by:

It also probably got some legs when I saw the Black Mirror Episode “The Entire History of You”, in which retinal contacts are a really significant (and terrifying) part of near-future life.

At some point I read about the creation of the mouse and the keyboard found that histories of these inputs technologies is old and iterative, despite how intuitive they may seem now.

In junior year of college, I found out I could rent a big chunky DJI phantom from my department and as my thumbs and some deep spatial part of my brain learned these new controls, it dawned on me all at once how adaptable human beings are, capable of extending their will into such a wide variety of complex instruments and that even using the body itself must be learned. In fact, veering last minute away from telephone lines, I felt very much like a child, and at night the sky buzzed behind my eyelids as if all this new data were being reviewed and processed. From that perspective, it seemed likely that we may have the potential to learn much more sophisticated and complex interfaces than mouses, keyboards, or even our bodies themselves, and software is ready to meet us wherever that complexity is, always more capable than the hardware gateways that allow us to orchestrate it day to day.

Three or four years ago, during the pandemic, it felt very natural to investigate and question my relationship with technology and question if there was a way to spend more time outside, less time sitting, and remove all possible barriers to life itself. I don’t that a glove can do all of that, and I’m glad this still has a spark in me in the form of this project, wherever it might lead!

Conversation with Shelby

I talked with my old friend Shelby, a PhD research psychologist who thinks a lot about how to better support neurodivergent groups. She thought that a device like this might be useful in helping provide an interface for the disabled, or maybe a useful sensory feedback device people with stimulation seeking behavior.

Conversation with Charles

Charles makes tensor boards. Charles brought up a variety of new concerns for this project which I really just dove into for impossible day and hadn’t thought of yet.

Distinguishing between Circuits

The first thing I realized while talking to him was that if the thumb was a voltage center, there would be no way to distinguish between the connections on the fingers of each hand. To do that, I would have to reverse the plan, and make each finger connected to a voltage sensor on the microcontroller, and the thumb the circuit.

Intermittent Polling of Circuit Voltage

Charles told me that the strategy that keyboards and, possibly, older versions of touchscreens used, was to intermittently send voltage through various circuits so that if a single voltage sensor connects with a circuit, it does so within the same loop in the program and therefore knows which circuit it is. HOWEVER he also told me that because of the property of capacitance (which I didn’t and still don’t know much about), this could be tricky if I didn’t give enough time for a circuit to “cool down”, leading to false readings. Which brings me to the next subject, which, being beyond me, is not the strategy I’ll start with (and is actually a much more modern approach I guess?) but might be the best strategy if I wasn’t a newcomer to circuitry, microcontrollers and physical computing.

Capacitance

Charles told me that something called capacitive sensors exist, but it sounded like they have not been around for very long. The idea is something along the lines of, if you have a conductor (a capacitive plate or “tank”), and you can monitor how much charge that capacitor is storing, you can also detect changes in it. A capacitor apparently changes in charge not only due to being loaded with electrons but also when the resistors around it change. This is sort of the idea behind one of those lamps that you can touch anywhere - when you touch a lamp like that, you aren’t completing a circuit in the way I originally hoped to with my input gauntlet. Instead, you are just changing the environment around a part of that circuit, and that change in an internal capacitor is detected. Disclaimer: I barely know what I’m talking about here! I would definitely like to learn more about this type of charge detection and to fill the holes in my understanding.

Charles told me a cool story about why capacitance is sometimes a better strategy for checking contact than circuit completion. He told me that apparently, older organs (like the kind you’d find in a church, or even an old theatre) used to play their various notes using circuit completion. However, over time, the components that were bashed against each other to complete these circuits corroded - possibly due some of the chemical effects of circuit completion - and they stopped working after a few decades. Checking capacitance, however, has no wear and tear because it can theoretically be done without contact.

Friday June 21st

Okay I have some new toys:

- Raspberry PI Pico W (Wireless)

- Conductive Tape

- Conductive Thread

The Raspberry Pi Pico W was recommended to me by the unpredictable and charming Greg Sadetsky for it’s small size and ability to connect to things wireless, which is the property I need most for this device to be an effective interface!

I’m starting this guide now from raspberrypi.org to get started with this device: Getting started with your Raspberry Pi Pico W

- Installed Thonny, a python IDE

- Tried to connect my PI and it didn’t work

- Tried another mini HDMI cable and that did work!

Pinout:

Getting started with the Raspberry Pi Pico!

- Not too difficult

- Using micropython compiled by a micropython IDE called Thonny recommended by Raspberry Pi organization

- Has Wifi, which it can use to send OSC on a local network

Here’s a video of sending potentiometer (also known as a twirly whirly) data via OSC:

Cool. So we can send data to things. That’s great. I also found that if I just renamed the Python file on the Pi to main.py, the Pi would run it on startup, and I could connect it to an external battery. So I have the capacity to:

- wireless power

- wireless OSC transmission

And it’s really just time to write the program and solder everything together to start generating the output data with some combination of circuit completion and gyroscopic (and other!) sensors!

//